Don't Just Eat Bitter, Start Demanding Better

Suffering for the sake of suffering serves no purpose.

“…I wish upon you ample doses of pain and suffering.”

- Jensen Huang, CEO and founder of Nvidia

“Greatness is not intelligence. Greatness comes from character. And character isn’t formed out of smart people, it’s formed out of people who suffered,” said Jensen Huang, CEO and founder of NVIDIA.

“Unfortunately, resilience matters in success,” he said. “I don’t know how to teach it to you except for I hope suffering happens to you.”

“To this day I use the phrase ‘pain and suffering’ inside our company with great glee,” Huang told Stanford students. “I mean that in a happy way, because you want to refine the character of your company. You want greatness out of them.”

There is a phrase in Chinese: 吃苦 (Chi Ku) that literally translates to “eating bitterness.” It means to persevere through hardship without complaint, even to the point of suffering. It means enduring through difficulty, so you can keep your eyes on the prize and stay focused. Koreans use the phrase 참아 (Cham Ah)” which means “take the pain” or “be patient.” A more common synonymous phrase in English might be “suck it up.” It implies that you need to experience mental or physical pain in order to reach your goals. Without the tasting the bitterness of the journey, you cannot taste the sweetness of success. The phrase comes from the idiom: “吃得苦中苦,方为人上人” or “If you can eat the most bitter of the bitter, then you can become the best of the best.” In Korean, the saying is: “고생 끝에 낙이 온다” which means delight comes at the end of difficulty. English speakers might translate this to “No pain, no gain” or that diamonds are formed under pressure.

This phrase applies in situations between teacher to student, parent to child, coach to athlete or manager to subordinate. It is a saying that is used as a form of encouragement during training or learning. Although it might be painful to wake up at the crack of dawn to run ten miles, you need to do it in order to finish a marathon. In order to get that promotion at work as an analyst, you must do the grunt work that no one else wants to do to earn the respect of your superiors. But as an immigrant or minority, this often translates to sucking it up when someone was racist, a manager mistreated you, or your green card application continues to be rejected for ten years. It means swallowing your pride constantly when things are unfair and you keep getting knocked down. To the point where you don’t even bother trying to get back up again.

Jensen Huang’s point is that you build character when you go through challenging times. Greatness comes from those who are resilient. Iron is forged in fire until it becomes malleable so it can be refined, strengthened and shaped into something new. You may have to take some hard falls in order to learn how to ride a bike or ski. You will wipeout many times when you are learning how to surf. But those scrapes and bruises are what it takes to get good at something. You grow and mature from failures and hardships.

The pendulum appears to have swung too far the other way in recent generations. Many of my contemporaries often criticize Millennials and Gen-Z for being soft, because they are unwilling to endure hardship or accept criticism. But the ideal lies somewhere in between. On the one hand, enduring hardship to no end is insane and sadistic. On the other hand, you will never achieve anything or succeed if you constantly give up when you stumble or times are hard.

Asians are often labeled “too nice” because they are always accommodating, which can be a euphemism for a doormat or punching bag. When you are constantly taking hits and never putting up a fight, people will have a tendency to walk all over you.

The danger is when you are asked to blindly obey without questioning or understanding why you are “suffering.” When you swallow too much bitterness, at some point you get so numb to it that you don’t know when enough is enough. Suffering for the sake of suffering is pointless. There needs to be an attainable goal or prize that you are reaching for to motivate you. If you are in a position where you have been “eating bitterness” with a path to nowhere, then you need to get off that path for your own good and sanity. Bad managers will take advantage of you if you let them. They will take credit for your work. They will avoid compensating you fairly. They will give you projects that they don’t want to do themselves. If you are constantly enduring suffering, then you will blindly accept all of this with or without complaint. Asians are often labeled “too nice” because they are always accommodating, which can be a euphemism for a doormat or punching bag. When you are constantly taking hits and never putting up a fight, people will have a tendency to walk all over you.

Blind Loyalty

It is a part of Asian culture to be fiercely loyal, sometimes to our own detriment. Our immigrant parents stayed at the same jobs for decades, and were most likely undercompensated for their contributions. They rarely challenged authority figures, because that was not in their nature. They were begrudgingly grateful for the opportunity. They swallowed their pride, because for many, there wasn’t a better option (because of the green card system or because they ran small businesses like gas stations or small shops). They may have complained in private, but they rarely complained or voiced their displeasure in public, much less advocate for themselves. They came from countries where they would be persecuted for speaking up. In the West, we say “the squeaky wheel gets the grease,” but in the East the saying is “the tallest blade of grass is the first to be cut.”

I’ve heard one too many stories from older Asian immigrants that were barely compensated for the sizable contributions they made to the companies they were loyal to for years. Many of us children of immigrants had parents who barely made six figures after working somewhere for two or three decades. We made more money coming out of college at our first jobs. There is no point in being loyal to a company or a person, when they would not think twice about laying you off when the time comes. Others will take advantage of you as long as you allow them to.

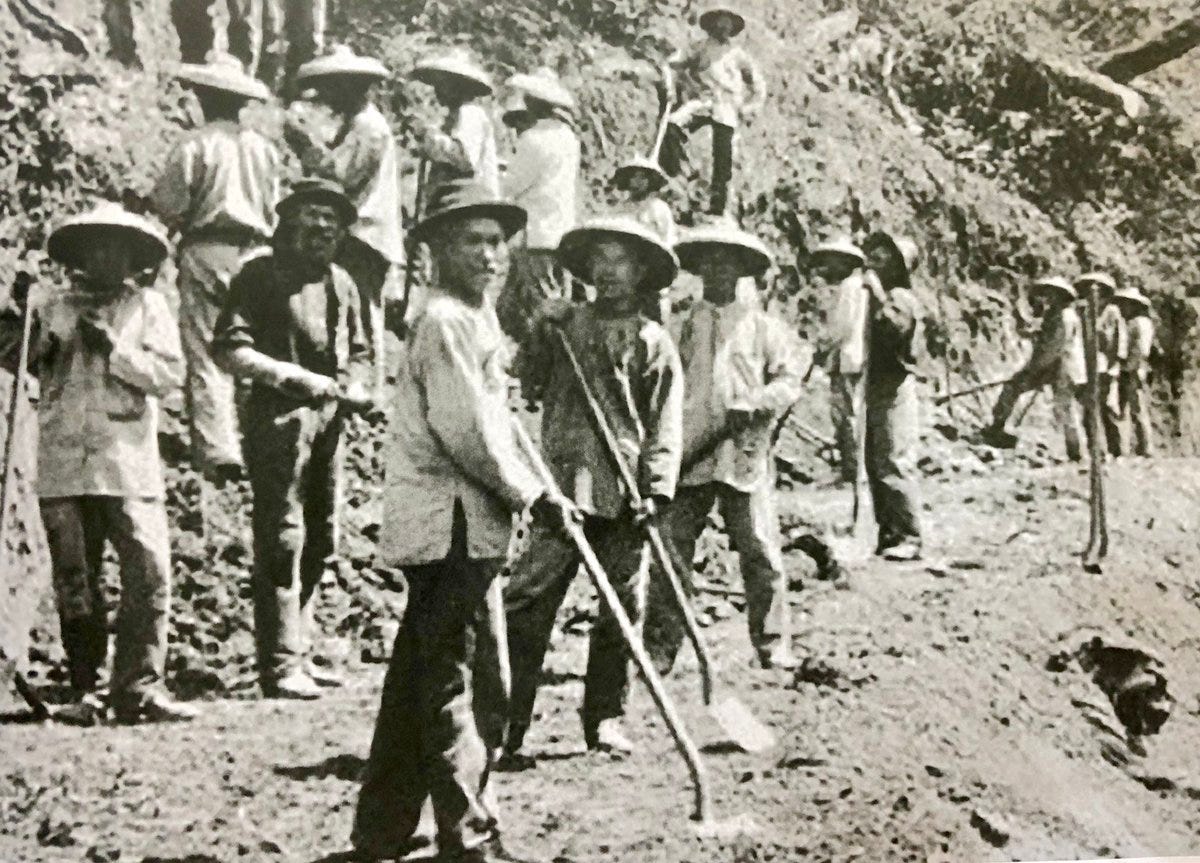

Nothing embodies “eating bitterness” and being exploited more than the Chinese railroad laborers that came to the U.S. in the 1800s to build a better life. The literally sacrificed their lives to build the Transcontinental Railroad only to have their contributions almost written out of history.

“The east railway was not nearly as challenging as the west, which was built mostly by Chinese workers, which required building tunnels through the Sierra Nevada Mountain range, with its long stretches of granite. The Chinese not only endured blasting through granite and grading roadbeds, but there were also dangerous avalanches, frequent snow drifts, illnesses and accidents, as well as Indian raids to contend with. The exhibit also sheds light on the cruel sinophobia and racism that the Chinese workers suffered. Unfair wages and other discriminatory practices were prevalent at the time, as were anti-Chinese protests and more violent acts.” - Remembering Chinese Laborers 145 Years Later

With this cultural background and history, it is not surprising then, that many second-generation Asian Americans stay at their jobs too long, even if they are miserable. Most people will start looking for new opportunities when any of the following apply:

They aren’t being compensated enough.

They don’t like their direct manager.

They aren’t doing work that is interesting to them.

But if you grow up with a mentality of “eating bitterness,” you are easily willing to put up with all three of these things. You are raised to believe that things “aren’t so bad” or that you shouldn’t complain about them. Meanwhile your peers and colleagues are vocalizing their displeasure to change their situation, or they are quitting to change their situation. They are constantly looking for better opportunities, because they believe they deserve them. If you believe that you’re supposed to endure suffering for the sake of enduring suffering, then it’s very likely you don’t actually believe you deserve anything. You end up assuming that this is just the way things are and you have no agency to do anything about your own circumstances. No one is going to change your situation for you, you have to change it yourself. If your manager doesn’t know that you’re unhappy, why should you assume that they will do anything different? They have other things to worry about. Why would someone promote you, pay you more or give you better projects if you are suffering in silence and seem perfectly content with what you have? If you believe your effort and quality work will speak for itself, your silence is even louder. This is a big reason why so many Asians are seen as ICs (individual contributors), because they work hard and have high quality output, and no manager wants to lose that.

Know Your Worth

The only way you are going to start speaking up for yourself is if you actually believe you deserve better. If you are content with settling for less than you deserve, then you have no reason to “complain.” The only way to find out your market value is to look for other opportunities and find out what you are truly worth. Apply to other jobs, talk to other people in your space, proactively assess if you’re being valued properly. Asians have the tendency to play themselves down, because they don’t want to disappoint others or embarrass (shame) themselves. In turn, they started to internalize and believe that they aren’t worthy or capable, so they begin to underestimate themselves. I see this all of the time with my founders in their pitch decks. Their projections are always extremely conservative, to the point where it is basically the worst-case scenario so they can minimize potential failure instead of maximizing potential success. This is all a result of the immigrant scarcity mindset and the fear of taking bold risks. They make themselves small to lower expectations. We need to break free of that mentality and increase our own expectations of ourselves. You can’t play big if you can’t dream big. Others can sense that, whether it’s when you are fundraising or if you are trying to get promoted. Why should anyone believe in you if you don’t even believe in yourself?

Use Your Voice

Advocating for yourself or vocalizing your displeasure is incongruous with enduring suffering without complaint. We no longer have to live under regimes that will punish you for standing out or voicing our discontent. Our parents endured and “sucked it up” to sacrificed so that we wouldn’t have to. They came from cultures that valued collective harmony above individuality. They came from places that valued meritocracy and the objective, rather than the subjective. They didn’t understand how the rules of the game were played here. They tried to play by the same rules that applied back home, which is why they were taken advantage of. Although our immigrant parents raised us with a strong work ethic, they also instilled those same rules of play in us, and we need to realize that’s not how it works here.

It’s hard to expect someone who never advocates for themselves in the workplace to walk into their manager’s office and demand a raise or a promotion. In high school or college, we were bold enough to go to our teachers and argue the case for a better grade aka “grade grubbing” because we knew that every point counted towards our final grade and our GPA. We had no problems advocating for ourselves back then, because we knew exactly how the game was played in school. We knew what our goals were. But in the workplace, it isn’t always clear what your goals are. For goal-oriented people, that can be extremely frustrating if not debilitating. It can be helpful to set micro goals (like mile markers in a race or yardage markers in football) for yourself to measure progress and hold yourself accountable to those personal goals. Or it might mean explicitly having a discussion with your manager about setting explicit goals, so you’re both on the same page on what you need to achieve. That way you can hold both yourself and your manager accountable to objective targets that can’t be argued away come time for your next raise or promotion evaluation.

In order to break the stereotype that Asians are too quiet and can’t lead, we need to be more vocal and demand more for ourselves. We need to stop believing that we don’t deserve it, because we haven’t “earned” it. Earning something at the workplace is extremely subjective, and is decided by your supervisor or manager. More often than not, you have to speak up to convince them that you’ve “earned” a promotion or a pay raise. We have to stop being okay with accepting scraps and crumbs. If you are not advocating for yourself, then you have already failed or accepted failure. Imposter syndrome is paralyzing because you don’t believe you are worthy and must be overestimating yourself. But if you are promoted to a certain position or trusted with an opportunity, then others clearly believe you deserve it and you are actually undermining yourself with self-doubt. You need to stop being the supporting character and embrace your role as the lead.

We need to stop believing that we don’t deserve it, because we haven’t “earned” it.

Jensen Huang was sent from Taiwan as a nine-year old with his older brother to live with their uncle in Tacoma, Washington. His uncle sent him to a boarding school in Kentucky that turned out to be a religious reform academy. He was bullied and called a “chink” every day. He would eventually be reunite with his parents a few years later. He studied electrical engineering at Oregon State where he worked as a dishwasher at Denny’s. Huang would graduate and work as a chip designer in Silicon Valley before running his own division and attending graduate school at Stanford in the evenings to get his master’s degree in 1992. When he was 30, he would start Nvidia in 1993 with two veteran chip designers and become CEO. After many ups and downs, thirty years later, Nvidia would become a multi-trillion dollar company and Huang is worth over $80 billion (the 17th richest person in the world). He endured suffering and hardship throughout his journey, but he had an intention and purpose, which ultimately paid off big time.

There is a fine line between building character by enduring hardships and being forged by the fire with a purpose and suffering for the sake of suffering. Bumps and bruises are expected when you climb to the top of the mountain. And you won’t make it to the top if you aren’t consistently vocal and advocating for yourself, because you will frequently need a helping hand to lift you up. They can only give you that hand if they can see and hear you and know that you want to be helped up. But if you are climbing a path to nowhere, it makes no sense to continue climbing and getting battered. Find another mountain to climb and don’t think twice about it, because loyalty doesn’t work both ways with your company. Look out for better opportunities and put yourself in a position where you can succeed, even if that means creating your own opportunities so that your suffering will lead to rewards that benefit you.

Thanks Dave for this. I read this a few months ago when you first published it, and reread it again tonight. Both times hit close to home, but this time, I really wondered how many times I would need to “relearn” the lesson. Hard to say I’ll master it as I may need to be a lifelong student, but perhaps practice makes perfect?

Thank you so much for this piece. I came to this via LinkedIn. I admit I’ve gotten frustrated with friends who complain to me about their managers, only for them to have no answer when I ask them what they’re going to do about it. And as someone who was recently laid off, too much resonates, ha…!